Renesansa u Škotskoj – razlika između verzija

Nema sažetka izmjene |

Nema sažetka izmjene |

||

| Red 2: | Red 2: | ||

{{renesansa}} |

{{renesansa}} |

||

'''Renesansa u Nizozemskim''' bila je kulturološki period [[sjevernoevropska renesansa|sjeverne renesanse]] koji se desio oko 16. vijeka u [[nizozemske|Nizozemskim]] (današnja [[Belgija]], [[Nizozemska]] i [[Francuska Flandrija]]). |

|||

The '''Renaissance in the Low Countries''' was a cultural period in the [[Northern Renaissance]] that took place in around the 16th century in the [[Low Countries]] (corresponding to modern-day [[Belgium]], the [[Netherlands]] and [[French Flanders]]). |

|||

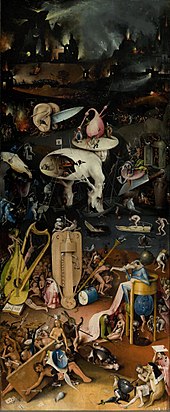

Kultura u Nizozemskim pri kraju 15. vijeka bila je pod utjecajem [[talijanska renesansa|talijanske renesanse]], putem trgovine kroz [[Bruges]] kojom se Flandrija obogatila. Njezina vlastela naručivala je umjetnike koji su postali poznati u čitavoj Evropi. U nauci je predvodio [[anatomija|anatom]] [[Andreas Vesalius]]; u [[kartografija|kartografiji]], karte [[Gerardus Mercator|Gerardusa Mercatora]] pomagale su istraživačima i navigatorima. U umjetnosti, [[holandsko i flamansko slikarstvo]] obuhvatalo je sve od neobičnih djela [[Hieronymus Bosch|Hieronymusa Boscha]] do prikaza svakodnevnog života [[Pieter Brueghel Stariji|Pietera Brueghela Starijeg]]. U arhitekturi, muzici i književnosti kultura Nizozemskih je također prešla u renesansni stil. |

|||

== Geopolitička situacija i pozadina == |

== Geopolitička situacija i pozadina == |

||

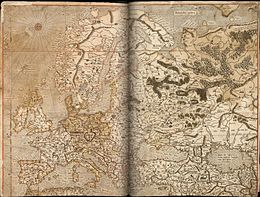

[[File:The Low Countries.png|thumb| |

[[File:The Low Countries.png|thumb|Karta koja pokazuje političku situaciju u Nizozemskim između 1556. i 1648. godine.]] |

||

Godine 1500. [[Sedamnaest provincija]] bile su u ličnoj uniji pod [[Burgundijska Nizozemska|burgundijskim vojvodama]], a sa [[grofovija Flandrija|flandrijskim]] gradovima kao gravitacionim centrima, kulturološki i ekonomski formirale su jedno od najbogatijih područja Evrope. Tokom tog vijeka ta regija također je prošla kroz značajne promjene. Ujedinjenje sa [[špansko carstvo|Španijom]] pod [[Karlo V., car Svetog Rimskog Carstva|Karlom V]], [[renesansni humanizam|humanizam]] i [[reformacija]] doveli su do pobune protiv španske vladavine i početka [[nizozemska revolucija|religijskog rata]]. Do kraja 16. vijeka sjeverna i [[južna Nizozemska]] bile su praktično podijeljene. Iako se taj raspad odrazio u vizuelnoj umjetnosti u [[slikarstvo holandskog zlatnog doba|holandskom zlatnom dobu]] na sjeveru i [[flamansko barokno slikarstvo|flamanskom baroku]] na jugu, ostala područja misli i dalje su se povezivala sa tokovima misli [[renesansa|renesanse]] u 16. vijeku. Postepeno, ravnoteža moći se pomjerila dalje od južne Nizozemske, koja je ostala pod španskom vlašću, do nastajuće [[Nizozemska Republika|Nizozemske Republike]].<ref name="Janson">{{cite book | last = Janson | first = H.W. |author2=Janson, Anthony F. | year = 1997 | title = History of Art | edition = 5th, rev. | publisher = [[Harry N. Abrams, Inc.]] | location = New York | url = http://www.abramsbooks.com | isbn = 0-8109-3442-6}}</ref> |

|||

Dva faktora odredila su sudbinu te regije u 16. vijeku. Prvi je bio ujedinjenje sa Španskim kraljevstvom 1496. kroz brak [[Philip I. Lijepi|Philipa Lijepog]] od [[vojvoda Burgundije|Burgundije]] i [[Juana I od Kastilje|Juane od Kastilje]]. Njihov sin, Karlo V., rođen u [[Gent]]u, naslijedio je najveće carstvo na svijetu, te je time [[Sedamnaest Provincija|Nizozemska]], iako istaknut dio carstva, postala ovisna o velikoj stranoj snazi. |

|||

Two factors determined the fate of the region in the 16th century. The first was the union with the kingdom of Spain through the 1496 marriage of [[Philip the Handsome]] of [[Duke of Burgundy|Burgundy]] and [[Juana of Castile]]. Their son, Charles V, born in [[Ghent]], would inherit the largest empire in the world, and the [[Seventeen Provinces|Netherlands]], although a prominent part of the empire, became dependent on a large foreign power. |

|||

Drugi faktor uključivao je religijske procese. [[Srednji vijek]] je dao nove oblike religioznog razmišljanja. Praksa [[Devotio Moderna]], na primjer, bila je naročito snažna u toj regiji, dok su kritike [[Katolička crkva|Katoličke crkve]] iz 16. vijeka koje su se proširile širom Evrope također zahvatile Nizozemske. [[renesansni humanizam|Humanisti]] poput [[Erazmo Roterdamski|Desideriusa Erasmusa od Rotterdama]] bili su kritični, ali ostali odani crkvi. Međutim, širenje [[reformacije]], koje je započeo [[Martin Luther]] 1517. godine, na kraju je dovelo do otvorenog rata. Reformacija, naročito ideje [[John Calvin|Johna Calvina]], dobile su značajnu podršku u Nizozemskim, te nakon [[ikonoklazam|izbijanja ikonoklazma]] 1566. Španija je pokušala zaustaviti protok i održati autoritet [[Tridentski koncil|posttridentske]] crkve putem sile uvevši [[Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, vojvoda Albe|Fernanda Álvareza od Toleda, vojvodu Albe]].<ref name="Kamen">{{cite book | last =Kamen | first = Henry | year = 2005 | title = Spain, 1469–1714, A Society of Conflict | edition = 3rd | publisher = Pearson Education | location = Harlow, United Kingdom | url = http://www.pearsoned.co.uk | isbn = 0-582-78464-6}}</ref> Represija koja je uslijedila dovela je do [[holandska pobuna|holandske pobune]], početka [[osamdesetogodišnji rat|Osamdesetogodišnjeg rata]], te osnivanja [[Nizozemska Republika|Nizozemske Republike]] u sjevernim provincijama. Nakon toga, Južna Nizozemska postala je utvrda [[kontrareformacije]], dok je [[kalvinizam]] postao glavna religija onih na snazi u Nizozemskoj Republici. |

|||

=== Utjecaj talijanske renesanse === |

=== Utjecaj talijanske renesanse === |

||

[[Image:Holbein-erasmus.jpg|thumb|upright|[[ |

[[Image:Holbein-erasmus.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Erazmo Roterdamski|Desiderius Erasmus]] 1523. godine]] |

||

Trade in the port of [[Bruges]] and the textile industry, mostly in Ghent, turned Flanders into the wealthiest part of Northern Europe at the end of the 15th century. The Burgundian court dwelled mostly in Bruges, Ghent and [[Brussels]]. The nobles and rich traders were able to commission artists, creating a class of highly skilled painters and musicians who were admired and requested around the continent.<ref name="Heughebaert">{{cite book | last = Heughebaert | first = H. |author2=Defoort, A. |author3=Van Der Donck, R. | year = 1998 | title = Artistieke opvoeding | publisher = Den Gulden Engel bvba. | location = Wommelgem, Belgium | isbn = 90-5035-222-7}}</ref> |

Trade in the port of [[Bruges]] and the textile industry, mostly in Ghent, turned Flanders into the wealthiest part of Northern Europe at the end of the 15th century. The Burgundian court dwelled mostly in Bruges, Ghent and [[Brussels]]. The nobles and rich traders were able to commission artists, creating a class of highly skilled painters and musicians who were admired and requested around the continent.<ref name="Heughebaert">{{cite book | last = Heughebaert | first = H. |author2=Defoort, A. |author3=Van Der Donck, R. | year = 1998 | title = Artistieke opvoeding | publisher = Den Gulden Engel bvba. | location = Wommelgem, Belgium | isbn = 90-5035-222-7}}</ref> |

||

Verzija na datum 23 juli 2019 u 16:23

Također uraditi: Renaissance in the Low Countries, Renaissance in Poland, Italian Renaissance, Portuguese Renaissance, Mid-Tudor Crisis, 19th-century London, History of London (1900–39)

| Renesansa |

|---|

"Atenska škola", Rafael, 1509–1511 |

| Teme |

| Regije |

Renesansa u Nizozemskim bila je kulturološki period sjeverne renesanse koji se desio oko 16. vijeka u Nizozemskim (današnja Belgija, Nizozemska i Francuska Flandrija).

Kultura u Nizozemskim pri kraju 15. vijeka bila je pod utjecajem talijanske renesanse, putem trgovine kroz Bruges kojom se Flandrija obogatila. Njezina vlastela naručivala je umjetnike koji su postali poznati u čitavoj Evropi. U nauci je predvodio anatom Andreas Vesalius; u kartografiji, karte Gerardusa Mercatora pomagale su istraživačima i navigatorima. U umjetnosti, holandsko i flamansko slikarstvo obuhvatalo je sve od neobičnih djela Hieronymusa Boscha do prikaza svakodnevnog života Pietera Brueghela Starijeg. U arhitekturi, muzici i književnosti kultura Nizozemskih je također prešla u renesansni stil.

Geopolitička situacija i pozadina

Godine 1500. Sedamnaest provincija bile su u ličnoj uniji pod burgundijskim vojvodama, a sa flandrijskim gradovima kao gravitacionim centrima, kulturološki i ekonomski formirale su jedno od najbogatijih područja Evrope. Tokom tog vijeka ta regija također je prošla kroz značajne promjene. Ujedinjenje sa Španijom pod Karlom V, humanizam i reformacija doveli su do pobune protiv španske vladavine i početka religijskog rata. Do kraja 16. vijeka sjeverna i južna Nizozemska bile su praktično podijeljene. Iako se taj raspad odrazio u vizuelnoj umjetnosti u holandskom zlatnom dobu na sjeveru i flamanskom baroku na jugu, ostala područja misli i dalje su se povezivala sa tokovima misli renesanse u 16. vijeku. Postepeno, ravnoteža moći se pomjerila dalje od južne Nizozemske, koja je ostala pod španskom vlašću, do nastajuće Nizozemske Republike.[1]

Dva faktora odredila su sudbinu te regije u 16. vijeku. Prvi je bio ujedinjenje sa Španskim kraljevstvom 1496. kroz brak Philipa Lijepog od Burgundije i Juane od Kastilje. Njihov sin, Karlo V., rođen u Gentu, naslijedio je najveće carstvo na svijetu, te je time Nizozemska, iako istaknut dio carstva, postala ovisna o velikoj stranoj snazi.

Drugi faktor uključivao je religijske procese. Srednji vijek je dao nove oblike religioznog razmišljanja. Praksa Devotio Moderna, na primjer, bila je naročito snažna u toj regiji, dok su kritike Katoličke crkve iz 16. vijeka koje su se proširile širom Evrope također zahvatile Nizozemske. Humanisti poput Desideriusa Erasmusa od Rotterdama bili su kritični, ali ostali odani crkvi. Međutim, širenje reformacije, koje je započeo Martin Luther 1517. godine, na kraju je dovelo do otvorenog rata. Reformacija, naročito ideje Johna Calvina, dobile su značajnu podršku u Nizozemskim, te nakon izbijanja ikonoklazma 1566. Španija je pokušala zaustaviti protok i održati autoritet posttridentske crkve putem sile uvevši Fernanda Álvareza od Toleda, vojvodu Albe.[2] Represija koja je uslijedila dovela je do holandske pobune, početka Osamdesetogodišnjeg rata, te osnivanja Nizozemske Republike u sjevernim provincijama. Nakon toga, Južna Nizozemska postala je utvrda kontrareformacije, dok je kalvinizam postao glavna religija onih na snazi u Nizozemskoj Republici.

Utjecaj talijanske renesanse

Trade in the port of Bruges and the textile industry, mostly in Ghent, turned Flanders into the wealthiest part of Northern Europe at the end of the 15th century. The Burgundian court dwelled mostly in Bruges, Ghent and Brussels. The nobles and rich traders were able to commission artists, creating a class of highly skilled painters and musicians who were admired and requested around the continent.[3]

This led to frequent exchanges between the Low Countries and Northern Italy. Examples are Italian architects Tommaso Vincidor and Alessandro Pasqualini, who worked in the Low Countries for most of their careers, Flemish painter Jan Gossaert, whose visit to Italy in 1508 in the company of Philip of Burgundy left a deep impression,[1] musician Adrian Willaert who made Venice into the most important musical centre of its time[3] (see Venetian School) and Giambologna, a Flemish sculptor who spent his most productive years in Florence.

Before 1500, the Italian Renaissance had little or no influence above the Alps. After this we begin to see Renaissance influences, but unlike the Italian Renaissance, Gothic elements remain important. The revival of the classical period is also not a central theme like in Italy, the "rebirth" shows itself more as a return to nature and earthly beauty.[3]

Renesansa u Nizozemskim

Umjetnost

15th-century painting in the Low Countries still shows strong religious influences, contrary to the Germanic painting. Even after 1500, when Renaissance influences begin to show, the influence of the masters from the previous century leads to a largely religious and narrative style of painting.

The first painter showing the marks of the new era is Hieronymus Bosch. His work is strange and full of seemingly irrational imagery, making it difficult to interpret.[1] Most of all it seems surprisingly modern, introducing a world of dreams that highly contrasts with the traditional style of the Flemish masters of his day.

After 1550 the Flemish and Dutch painters begin to show more interest in nature and in beauty an sich, leading to a style that incorporates Renaissance elements, but remains very far from the elegant lightness of Italian Renaissance art,[3] and directly leads to the themes of the great Flemish and Dutch Baroque painters: landscapes, still lifes and genre painting - scenes from everyday life.[1]

This evolution is seen in the works of Joachim Patinir and Pieter Aertsen, but the true genius among these painters was Pieter Brueghel the Elder, well known for his depictions of nature and everyday life, showing a preference for the natural condition of man, choosing to depict the peasant instead of the prince.

The Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, now thought to be an early copy, combines several elements of northern Renaissance painting. It hints at the renewed interest for antiquity (the Icarus legend), but the hero Icarus is hidden away in the background. The main actors in the painting are nature itself and, most prominently, the peasant, who does not even look up from his plough when Icarus falls. Brueghel shows man as an anti-hero, comical and sometimes grotesque.[3]

Arhitektura i skulptura

As in painting, Renaissance architecture took some time to reach the High Countries, and did not entirely supplant the Gothic elements. The most important sculptor in the Southern Netherlands was Giambologna, who spent most of his career in Italy. An architect directly influenced by the Italian masters was Cornelis Floris de Vriendt, who designed the city hall of Antwerp, finished in 1564.

In sculpture, however, 15th-century Flemish artists, while adhering to Christian subjects, developed techniques and a naturalistic style which compares favorably to the work of early-Renaissance Italian contemporaries such as Donatello. Claus Sluter (fl. ~1400) produced works such as the Well of Moses with a dynamism almost unknown at the turn of the 15th century; and Dutch-born Nikolaus Gerhaert van Leyden (b. ~1420) made sculptures such as "Man Meditating" which even today appear more "modern" than does Italian Quattrocento carving.

In the early-17th-century Dutch Republic, Hendrick de Keyser plays an important role in developing the Amsterdam Renaissance style, not slavishly following the classical style but incorporating many decorative elements, giving a result that could also be categorized as Mannerism. Hans Vredeman de Vries was another important name, primarily as a garden architect.

Muzika

While in painting, the Low Countries were leading Northern Europe, in music the "Franco-Flemish" or "Dutch School" dominated all of Europe. In the early Renaissance, polyphonic musicians and composers from the Low Countries, like Johannes Ciconia, were working at all the European courts and churches. Educated in the church and cathedral schools of their own region, they spread out and would bring their style to the whole continent, so that by the late renaissance a unified musical style emerged throughout Europe.[3]

Although there is no reference to antiquity, there is a clear Flemish "Renaissance consciousness", as indicated by the words of Flemish theorist Johannes Tinctoris, who said of these composers: "Although it is beyond belief, nothing worth listening to had been composed before their time.".[1]

Renaissance elements in the music are the return from the "divine origin" of music to earthly beauty and sensory joy. The music becomes more structured, balanced and melodic. Whereas in the Middle Ages the choice of instruments was free, composers now start to organize instruments into homogenous groups, and write music specifically for certain arrangements.[3]

Josquin des Prez was the most celebrated composer during the High Renaissance, and during his career enjoyed the patronage of three popes. Equally at ease in secular and religious music, he can be considered the first musical genius we know of.[1]

Other important composers from the Low Countries were Guillaume Dufay, Johannes Ockeghem, Jacob Clemens non Papa and Adrian Willaert. Orlande de Lassus, a Fleming who had lived in Italy as a youth and spent most of his career in Munich, was the leading composer of the late Renaissance.

Književnost

- Vidi takođe: Dutch Renaissance and Golden Age literature

In the middle of the 16th century, a group of rhetoricians (see Medieval Dutch literature) in Brabant and Flanders attempted to put new life into the stereotyped forms of the preceding age by introducing in original composition the new-found branches of Latin and Greek poetry. The leader of these men was Johan Baptista Houwaert, who was led by an unbounded love of classical and mythological fancy.[4]

The most important genre was music publishing, especially psalms. The Souterliedekens publication is one of the most important sources for the reconstruction of Renaissance folksongs. Later publishing was heavily influenced by the rebellion against the Spanish: heroic battle songs and political ballads ridiculing the Spanish occupants.

Best remembered of the writers is Philips van Marnix, lord of Sint-Aldegonde, who was one of the leading spirits in the war of Dutch independence. He wrote a satire on the Roman Catholic Church, started to work on a Bible translation and allegedly wrote the lyrics to the Dutch national anthem.

Other important names are Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert, Hendrick Laurensz. Spieghel and Roemer Visscher. Inevitably, their works and career were very much determined by the struggle between Reformation and the Catholic Church.

Nauka

The new age presents itself in science as well. Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius's life typically shows both the new possibilities and the troubles that came with them. He delivered ground-breaking work in rediscovering the human body, after centuries of disregard for it. This earned him great respect from some, but also caused several enquiries into his methods (dissection of the human body) and the religious implications of his work.

While Vesalius performed ground-breaking work in rediscovering the human body, Gerardus Mercator, as one of the leading cartographers of his time, did the same for rediscovering the outside world. Mercator too came into trouble with the Church because of his beliefs, and spent several months in jail after a conviction for heresy.

Both scientists' lives show how the Renaissance scientist is not afraid of challenging what has been taken for granted for centuries, and how this leads to problems with the all-powerful catholic church.

Though the invention of the printing press by Laurens Janszoon Coster in the 1430s appears to be a romantic notion, the Low Countries had an early start in printing. By 1470 a printing press was in use in Utrecht, where the first dated extant book was printed in 1473, while the first book in the Dutch language was the 1477 Delft Bible. By 1481 the Low Countries had printing shops in 21 cities and towns.[5] Famous publishing houses like those of Christoffel Plantijn in Antwerp from 1555 on, Petrus Phalesius the Elder in Leuven from 1553, and the House of Elzevir in Leiden from around 1580 turned the Low Countries into a regional center of publishing.

Povezano

Politička situacija

- Burgundian Netherlands

- Seventeen Provinces

- Dutch Republic – Dutch Golden Age

- Southern Netherlands

- Eighty Years' War

Umjetnost

- Early Netherlandish Painting

- Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting

- Flemish painting

- Dutch School (music)

- Dutch Renaissance and Golden Age literature

- List of Flemish painters

- List of Dutch painters

Reference

- ↑ 1,0 1,1 1,2 1,3 1,4 1,5 Janson, H.W.; Janson, Anthony F. (1997). History of Art (5th, rev. izd.). New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.. ISBN 0-8109-3442-6.

- ↑ Kamen, Henry (2005). Spain, 1469–1714, A Society of Conflict (3rd izd.). Harlow, United Kingdom: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-78464-6.

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 3,2 3,3 3,4 3,5 3,6 Heughebaert, H.; Defoort, A.; Van Der Donck, R. (1998). Artistieke opvoeding. Wommelgem, Belgium: Den Gulden Engel bvba.. ISBN 90-5035-222-7.

- ↑ Šablon:EB1911

- ↑ E. L. Eisenstein: The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge, 1993 pp.13–17, quoted in: Angus Maddison: Growth and Interaction in the World Economy: The Roots of Modernity, Washington 2005, p.17f.