Renesansa u Škotskoj – razlika između verzija

Nema sažetka izmjene |

Nema sažetka izmjene |

||

| Red 1: | Red 1: | ||

'''Također uraditi:''' |

'''Također uraditi:'''German Renaissance, Renaissance in the Low Countries, Renaissance in Poland, Italian Renaissance, Portuguese Renaissance, Mid-Tudor Crisis, 19th-century London, History of London (1900–39) |

||

{{Renaissance}} |

|||

[[File:Albrecht Dürer - Portrait of Maximilian I - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|right|265px|''[[Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I]]'' (reigned: 1493–1519), the first Renaissance monarch of the [[Holy Roman Empire]], by [[Albrecht Dürer]], 1519]] |

|||

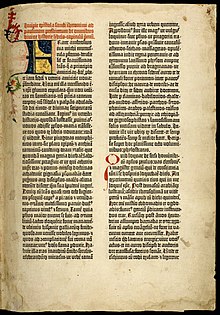

[[File:Gutenberg bible Old Testament Epistle of St Jerome.jpg|thumb|First page of the first volume of a copy of the [[Gutenberg Bible]] in Texas]] |

|||

'''Njemačka renesansa''', dio [[sjeverna renesansa|sjeverne renesanse]], bila je kulturološki i umjetnički pokret koji se proširio među [[njemačka|njemačkim]] misliocima u 15. i 16. vijeku i koji se razvio iz [[talijanska renesansa|talijanske renesanse]]. Mnoga područja umjetnosti i nauka bila su pod utjecajem, prije svega [[Renesansni humanizam u Sjevernoj Evropi|širenjem renesansnog humanizma u razne njemačke države i kneževine]]. Napravljeni su mnogi koraci naprijed u područjima arhitekture, umjetnosti i nauka. Njemačka je dovela do dvije pojave koje su dominirale 16. vijekom u čitavoj Evropi: štamparstvo i [[reformacija|protestantsku reformaciju]]. |

|||

{{italic title}} |

|||

{{Infobox book |

|||

| name = ''De humani corporis fabrica'' |

|||

| image = File:Vesalius Fabrica fronticepiece.jpg |

|||

| caption = Naslovna strana. Puni naziv je ''Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, scholae medicorum Patauinae professoris, de Humani corporis fabrica Libri septem'' (Andreas Vesalius od Brisela, profesor Medicinske škole u Padovi, o tkanju Ljudskog tijela u sedam Knjiga). |

|||

| author = [[Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

| illustrator = '[[Ticijan]]ov studij' |

|||

| country = Italija |

|||

| subject = [[Anatomija]] |

|||

| genre = Ilustrirani udžbenik |

|||

| publisher = Medicinska škola, [[Padova]] |

|||

| pub_date = 1543 |

|||

| pages = |

|||

| awards = |

|||

| oclc = |

|||

| dewey = |

|||

| congress = |

|||

| wikisource = |

|||

}} |

|||

[[Image:Vesalius Fabrica p184.jpg|thumb|upright|''Fabrica'' je poznata po svojim vrlo detaljnim ilustracijama ljudskih [[disekcija]], često u [[alegorija|alegorijskim]] pozama.]] |

|||

Jedan od najvažnijih njemačkih humanista bio je [[Conrad Celtes|Konrad Celtis]] (1459–1508). Celtis je studirao u [[Keln]]u i [[Heidelberg]]u, a kasnije je putovao čitavom Italijom prikupljajući latinske i grčke rukopise. Pod velikim utjecajem [[Tacit]]a, koristio je knjigu ''[[Germania (book)|Germania]]'' kako bi uveo [[historija Njemačke|njemačku historiju]] i geografiju. Na kraju je posvetio svoje vrijeme poeziji, gdje je hvalio Njemačku na latinskom jeziku. Još jedna važna ličnost bio je [[Johann Reuchlin]] (1455–1522) koji je studirao na različitim mjestima u Italiji i kasnije podučavao grčki jezik. Studirao je [[hebrejski jezik]], sa ciljem da pročisti kršćanstvo, ali je naišao na protivljenje crkve. |

|||

'''''De humani corporis fabrica libri septem''''' ([[latinski]] za "O tkanju ljudskog tijela u sedam knjiga") je niz knjiga o [[ljudsko tijelo|ljudskoj anatomiji]] koje je napisao [[Andreas Vesalius]] (1514–1564) i objavio 1543. godine. Predstavljale su glavni napredak u [[historija anatomije|historiji anatomije]] nad dugo vremena dominantnim djelima [[Galen]]a i predstavljale su se kao takve. |

|||

Najvažniji umjetnik njemačke renesanse je [[Albrecht Dürer]], naročito poznat po svojoj [[štampa|štampi]] u [[drvorez]]u i [[gravura|gravuri]], koja se proširila čitavom Evropom, crtežima i slikanim portretima. U važnu arhitekturu iz ovog perioda spadaju [[Landshut Residence]], [[Heidelberg Castle]], [[Augsburg Town Hall]] kao i [[Antiquarium]] od [[Munich Residenz]], najveća renesansna dvorana sjeverno od Alpa.<ref>[[Munich Residenz]]</ref>{{Circular reference|date=March 2019}} |

|||

Zbirka knjiga zasniva se na njegovim predavanjima u [[Padovanski univerzitet|Padovi]], tokom kojih se udaljavao od uobičajene prakse diseciranja trupla kako bi pokazao ono o čemu je govorio. [[Disekcija|Disekcije]] su prethodno izvodili [[hirurzi-brijači]] pod uputama doktora medicine, za kojeg se nije očekivalo da izvodi ručni rad. Vesalijev ''[[remek-djelo|magnum opus]]'' predstavlja pažljiv pregled organa i potpune strukture ljudskog tijela. To ne bi bilo moguće bez mnogih napredaka do kojih je došlo u [[renesansa|renesansi]], uključujući umjetnički razvoj u vizuelnom predstavljanju i tehnički razvoj štampanja sa obrađenim [[drvorez]]nim gravurama. Zbog tih razvoja i njegovog pažljivog, direktnog sudjelovanja, Vesalije je uspio stvoriti ilustracija bolje od bilo kojih prethodno stvorenih. |

|||

== |

== Pozadina == |

||

[[Renesansa]] je većinom vođena obnovljenim interesom za klasično učenje i također je bila rezultat brzog ekonomskog razvoja. Na početku 16. vijeka, Njemačka (što se odnosi na zemlje sadržane unutar Svetog Rimskog Carstva) je bila jedno od najprosperitetnijih područja u Evropi unatoč relativno niskom nivou urbanizacije u usporedbi sa Italijom i Nizozemskom.<ref>''German economic growth, 1500–1850'', Ulrich Pfister</ref>{{Full|date=November 2015}} Imala je koristi od bogatstva određenih sektora poput metalurgije, rudarstva, bankarstva i tekstila. Još važnije, štampanje knjiga razvilo se u Njemačkoj i [[Global spread of the printing press|njemački štampači dominirali]] su novom trgovinom knjigama u većini drugih država do duboko u 16. vijeku. |

|||

Vesalije je rasporedio svoja djela u sedam knjiga. |

|||

== Umjetnost == |

|||

=== Knjiga 1: Kosti i hrskavice === |

|||

[[File:HMF Duerer Gruenewald Harrich Heller-Altar DSC 6312.jpg|thumb|The Heller altar by [[Albrecht Dürer]]]] |

|||

Prva knjiga sačinjava oko četvrtinu čitave zbirke. Ona predstavlja Vesalijeva zapažanja o ljudskim kostima i hrskavici, koje je [[krađa trupala|prikupljao sa groblja]]. Ona pokriva fizički izgled ljudskih kostiju i diferencijaciju ljudskih kostiju i hrskavice po funkciji. U svakom poglavlju Vesalije vrlo detaljno opisuje kosti, objašnjavajući njihove fizičke osobine na različite načine. U prvim poglavljima, Vesalije "daje generalne aspekte kostiju i skeletne organizacije, baveći se razlikama u teksturi, čvrstoći i otpornosti između kosti i hrskavice; objašnjavajući složene razlike između tipova zglobova i pregledajući neke osnovne elemente tehnika opisivanja i terminologije." Značajna tema ove knjige je da li je [[Galen]] ispravno opisao kosti ljudskog skeleta. Kada je Vesalije predavao o ljudskom skeletu, također je morao predstaviti kosti životinja kako bi dao vjerodostojnost Galenovim zapažanjima. |

|||

The concept of the Northern Renaissance or German Renaissance is somewhat confused by the continuation of the use of elaborate Gothic ornament until well into the 16th century, even in works that are undoubtedly Renaissance in their treatment of the human figure and other respects. Classical ornament had little historical resonance in much of Germany, but in other respects Germany was very quick to follow developments, especially in adopting [[printing]] with [[movable type]], a German invention that remained almost a German monopoly for some decades, and was [[Global spread of the printing press|first brought to most of Europe]], including France and Italy, by Germans. {{Citation needed|date=August 2015}} |

|||

[[File:Vesalius Fabrica p163.jpg|thumb|left|upright|''De humani corporis fabrica'' (1543), strana 163]] |

|||

[[Printmaking]] by [[woodcut]] and [[engraving]] was already more developed in Germany and the [[Low Countries]] than elsewhere in Europe, and the Germans took the lead in developing book illustrations, typically of a relatively low artistic standard, but seen all over Europe, with the woodblocks often being lent to printers of editions in other cities or languages. The greatest artist of the German Renaissance, [[Albrecht Dürer]], began his career as an apprentice to a leading workshop in Nuremberg, that of [[Michael Wolgemut]], who had largely abandoned his painting to exploit the new medium. Dürer worked on the most extravagantly illustrated book of the period, the [[Nuremberg Chronicle]], published by his godfather [[Anton Koberger]], Europe's largest printer-publisher at the time.<ref name="Bartrum 2002">Bartrum (2002)</ref> |

|||

=== Knjiga 2: Tetive i mišići === |

|||

Ovdje Vesalije opisuje strukturu mišića, struktura koje služe stvaranju kretanja tijelom, te materijala koji drže zglobove povezanim. Posmatrajući mesare koji režu meso, bio je u prilici inkorporirati vještine koje su oni koristili u diseciranju ljudskog tijela. Predstavljen je red kojim se disecira ljudsko tijelo kako bi se efikasno posmatrao svaki mišić. Svaka ilustracija prikazuje sve dublji pogled na ljudsko tijelo koji se može slijediti tokom diseciranja ljudskog tijela. Vesalije također spominje instrumente neophodne za izvođenje disekcije. Vesalije tu počinje opisivati kako se Galenovi anatomski opisi ne poklapaju sa njegovim vlastitim zapažanjima. Kako bi pokazao poštovanje prema Galenu, on sugerira da je Galenova upotreba anatomske strukture zapravo tačna, ali ne za ljude. Čak nastavlja opisivati neke od struktura na isti način na koji bi to uradio Galen. |

|||

After completing his apprenticeship in 1490, Dürer travelled in Germany for four years, and Italy for a few months, before establishing his own workshop in Nuremberg. He rapidly became famous all over Europe for his energetic and balanced woodcuts and engravings, while also painting. Though retaining a distinctively German style, his work shows strong Italian influence, and is often taken to represent the start of the German Renaissance in visual art, which for the next forty years replaced the Netherlands and France as the area producing the greatest innovation in Northern European art. Dürer supported [[Martin Luther]] but continued to create [[Madonna (art)|Madonnas]] and other Catholic imagery, and paint portraits of leaders on both sides of the emerging split of the [[Protestant Reformation]].<ref name="Bartrum 2002" /> |

|||

=== Knjiga 3: Vene i arterije, Knjiga 4: Nervi === |

|||

[[File:Mathis Gothart Grünewald 022.jpg|The Crucifixion of Jesus Christ|right|thumb|''The [[Crucifixion]]'', central panel of the [[Isenheim Altarpiece]] by [[Matthias Grünewald]].|left]] |

|||

U Knjigama 3 i 4, Vesalije opisuje vene, arterije i nerve kao sudove, ali spominje njihovu različitu fizičku strukturu: vene i arterije sadrže prazan kanal, ali ne i nervi. Vesalije opisuje put kojim zrak putuje kroz pluća i srce. On opisuje taj proces kao "drvo čija se debla razdjeljuju u grane i grančice". On također opisuje kako tijelo sadrži četiri vene (portalna vena, venae cavae, arteriji slična vena [sada poznata kao [[plućna vena]]], te umbilarna vena) i dvije arterije (aorta i veni slična arterija [sada poznata kao [[plućna arterija]]]) kao glavne sudove koji se granaju u manje vene i arterije. Vesalije popisuje oko šest stotina sudova u svom tabelisanju arterija, vena i nerava, ali ne spominje manje sudove u rukama i stopalima, krajnje sudove kožnih nerava ili sudove pluća i jetre. |

|||

Dürer died in 1528, before it was clear that the split of the Reformation had become permanent, but his pupils of the following generation were unable to avoid taking sides. Most leading German artists became Protestants, but this deprived them of painting most religious works, previously the mainstay of artists' revenue. [[Martin Luther]] had objected to much Catholic imagery, but not to imagery itself, and [[Lucas Cranach the Elder]], a close friend of Luther, had painted a number of "Lutheran altarpieces", mostly showing the [[Last Supper]], some with portraits of the leading Protestant divines as the [[Twelve Apostles]]. This phase of Lutheran art was over before 1550, probably under the more fiercely [[aniconic]] influence of [[Calvinism]], and religious works for public display virtually ceased to be produced in Protestant areas. Presumably largely because of this, the development of German art had virtually ceased by about 1550, but in the preceding decades German artists had been very fertile in developing alternative subjects to replace the gap in their order books. Cranach, apart from portraits, developed a format of thin vertical portraits of provocative nudes, given classical or Biblical titles.<ref>Snyder, Part III, Ch. XIX on Cranach, Luther etc.</ref> |

|||

=== Knjiga 5: Organi hranjenja i generisanja === |

|||

Vesalije daje detaljne opise organa hranjenja, mokraćni sistem i muške i ženske reproduktivne sisteme. Digestivni i reproduktivni sistemi čine oko četrdeset procenata ove knjige, a opis bubrežnog sistema i ispravne tehnike za njegovu disekciju čine ostatak. U konačnom poglavlju, najdužem u čitavoj zbirci, Vesalije daje detaljna, postepena uputstva o tome kako disecirati abdominopelvičke organe. U prvoj polovini knjige, Vesalije opisuje peritoneum, jednjak, stomak, omentum, iznutrice i mezenterijum. Potom opisuje jetru, žučnu kesu i slezenu. Konačno, opisuje bubrege, mokraćnu bešiku i mokraćovode. Iako Vesalije nije bio upoznat sa anatomijom trudnoće, on pruža ilustracije placente i fetalne membrane, te pravi anatomske reference na Galena upoređujući pseće i ljudske reproduktivne organe. |

|||

Lying somewhat outside these developments is [[Matthias Grünewald]], who left very few works, but whose masterpiece, his ''[[Isenheim Altarpiece]]'' (completed 1515), has been widely regarded as the greatest German Renaissance painting since it was restored to critical attention in the 19th century. It is an intensely emotional work that continues the German Gothic tradition of unrestrained gesture and expression, using Renaissance compositional principles, but all in that most Gothic of forms, the multi-winged [[triptych]].<ref>Snyder, Ch. XVII</ref> |

|||

=== Knjiga 6: Srce i povezani organi, Knjiga 7: Mozak === |

|||

[[File:Albrecht Altdorfer 007.jpg|thumb|220px|left|[[Albrecht Altdorfer]] (c.1480–1538), ''Danube landscape near Regensburg'' c. 1528, one of the earliest Western pure landscapes, from the [[Danube school|Danube School]] in southern [[Germany]].]] |

|||

[[File:Vesalius 609c.png|thumb|upright|''De humani corporis fabrica'', figura na ploči 609, pod kontrastom]] |

|||

The [[Danube school|Danube School]] is the name of a circle of artists of the first third of the 16th century in [[Bavaria]] and Austria, including [[Albrecht Altdorfer]], [[Wolf Huber]] and [[Augustin Hirschvogel]]. With Altdorfer in the lead, the school produced the first examples of independent [[landscape art]] in the West (nearly 1,000 years after China), in both paintings and prints.<ref>Wood, 9 – this is the main subject of the whole book</ref> Their religious paintings had an [[expressionist]] style somewhat similar to Grünewald's. Dürer's pupils [[Hans Burgkmair]] and [[Hans Baldung Grien]] worked largely in prints, with Baldung developing the topical subject matter of [[witch]]es in a number of enigmatic prints.<ref>Snyder, Ch. XVII, Bartrum, 1995</ref> |

|||

Ove knjige opisuju strukturu i funkciju srca i dišnih organa, te mozak i njegove pokrivače, oko i senzorne organe, te nerve udova. Poglavlje je također posvećeno disekciji oka. Vesalije veoma detaljno opisuje organe tijela komentirajući "o različitoj snazi povezanosti pleure za zidove grudnog koša, snažnoj povezanosti perikarda sa dijafragmom, obliku i usmjerenju srčanih komora i opisu polumjesečastih zalistaka." On završava svaku knjigu sa poglavljem o ispravnom načinu diseciranja srca i mozga. |

|||

[[Hans Holbein the Elder]] and his brother Sigismund Holbein painted religious works in the late Gothic style. Hans the Elder was a pioneer and leader in the transformation of German art from the Gothic to the Renaissance style. His son, [[Hans Holbein the Younger]] was an important painter of portraits and a few religious works, working mainly in England and Switzerland. Holbein's well known series of small woodcuts on the ''[[Dance of Death]]'' relate to the works of the [[Little Masters]], a group of printmakers who specialized in very small and highly detailed engravings for bourgeois collectors, including many erotic subjects.<ref>Snyder, Ch. XX on the Holbeins, Bartrum (1995), 221–237 on Holbein's prints, 99–129 on the Little Masters</ref> |

|||

== Galenove greške == |

|||

Galen, značajan [[grci|grčki]] [[ljekar]], [[hirurg]] i [[filozofija|filozof]] u [[Rimsko Carstvo|Rimskom Carstvu]], pisao je o anatomiji među mnogim drugim temama, ali njegov rad ostao je većinom neprovjeren do Vesalijevog vremena. ''Fabrica'' je ispravila neke od Galenovih najvećih grešaka, uključujući ideju da veliki krvni sudovi potiču iz jetre. Tokom proučavanja ljudskog trupla, Vesalije je otkrio da su Galenova zapažanja bila nedosljedna njegovim, zbog Galenove upotrebe životinjskih (psećih i majmunskih) trupala. Čak i sa svojim instrumentima, međutim, Vesalije se držao nekih Galenovih grešaka, poput ideje da su različiti tipovi krvi proticali kroz vene u odnosu na arterije. Ta Galenova zabluda ispravljena je u Evropi tek sa radom [[William Harvey|Williama Harveya]] o [[cirkulatorni sistem|kruženju krvi]] (''[[De Motu Cordis]]'', 1628). |

|||

[[File:Vesalius Fabrica p372.jpg|thumb|upright|''De humani corporis fabrica'' (1543), strana 372]] |

|||

The outstanding achievements of the first half of the 16th century were followed by several decades with a remarkable absence of noteworthy German art, other than accomplished portraits that never rival the achievement of Holbein or Dürer. The next significant German artists worked in the rather artificial style of [[Northern Mannerism]], which they had to learn in Italy or Flanders. [[Hans von Aachen]] and the Netherlandish [[Bartholomeus Spranger]] were the leading painters at the Imperial courts in [[Vienna]] and Prague, and the productive Netherlandish [[Sadeler family]] of engravers spread out across Germany, among other counties.<ref>Trevor-Roper, Levey</ref> |

|||

== Objava == |

|||

In Catholic parts of South Germany the Gothic tradition of wood carving continued to flourish until the end of the 18th century, adapting to changes in style through the centuries. [[Veit Stoss]] (d. 1533), [[Tilman Riemenschneider]] (d.1531) and [[Peter Vischer the Elder]] (d. 1529) were Dürer's contemporaries, and their long careers covered the transition between the Gothic and Renaissance periods, although their ornament often remained Gothic even after their compositions began to reflect Renaissance principles.<ref>Snyder, 298–311</ref> |

|||

=== Izdanje iz 1543. godine === |

|||

Vesalije je objavio rad u 28. godini života, veoma se potrudivši da osigura njegov kvalitet, te ga je posvetio [[Karlo V., car Svetog Rimskog Carstva|Karlu V., caru Svetog Rimskog Carstva]]. Više od 250 ilustracija velike su umjetničke vrijednosti i današnji učenjaci ih većinom pripisuju "[[Ticijan]]ovom studiju" umjesto [[Jan Van Calcar|Johannesu Stephanusu od Calcara]], koji je pružio crteže za Vesalijeve prethodne traktate. Drvorezi su bili mnogo bolji od ilustracija u tadašnjim anatomskim atlasima, koje nikada nisu pravili sami profesori anatomije. Drvorezni blokovi prenosili su se u [[Basel|Basel, u Švicarskoj]], budući da je Vesalije želio da djelo bude objavljeno od strane jednog od najistaknutijih štampara tog vremena, [[Johannes Oporinus|Johannesa Oporinusa]]. Vesalijeva pisana uputstva Oporinusu (''iter'') bila su toliko vrijedna da ih je štampar odlučio uključiti. Ilustracije su bile urezane na drvenim blokovima, što je omogućilo vrlo detaljne opise.<ref>Brian S. Baigrie ''Scientific Revolutions'', strane 40–49 sadrži više informacija i prevod Vesalijevog predgovora.</ref> |

|||

== Arhitektura == |

|||

=== Izdanje iz 1555. godine === |

|||

[[File:Heidelberg - Heidelberg Schloss 2015-09-11 19-23-06.JPG|thumb|[[Heidelberg Castle]]]] |

|||

Drugo izdanje objavljeno je 1555. godine. Pribilješke u kopiji tog izdanja doniranog [[Biblioteci rijetkih knjiga Thomas Fisher]], [[Univerzitet u Torontu]], identificirane su kao Vesalijeve vlastite, pokazujući da je razmišljao o trećem izdanju, koje nikada nije napravljeno.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.news.utoronto.ca/u-t-acquires-annotated-copy-vesaliuss-great-anatomical-book |title=U of T acquires annotated copy of Vesalius's great anatomical book |publisher=University of Toronto |date=2013-03-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Juleum Helmstedt.jpg|thumb|[[University of Helmstedt|Juleum]] in [[Helmstedt]] (built 1592), an example of [[Weser Renaissance]] architecture]] |

|||

[[Renaissance Architecture]] in Germany was inspired first by German philosophers and artists such as [[Albrecht Dürer]] and [[Johannes Reuchlin]] who visited Italy. Important early examples of this period are especially the [[Landshut Residence]], the [[Heidelberg Castle|Castle]] in [[Heidelberg]], [[Schloss Johannisburg|Johannisburg Palace]] in [[Aschaffenburg]], [[Schloss Weilburg]], the [[Augsburg Town Hall|City Hall]] and [[Fuggerhäuser|Fugger Houses]] in [[Augsburg]] and [[St. Michael's Church, Munich|St. Michael]] in [[Munich]], the largest Renaissance church north of the Alps. |

|||

== Prijem == |

|||

Uspjeh ''Fabrica'' nadoknadio je značajne troškove tog djela i donio Vesaliju slavu na nivou čitave Evrope, djelimično zahvaljujući jeftinim neovlaštenim kopijama. Imenovan je ljekarom [[Karlo V., car Svetog Rimskog Carstva|cara Svetog Rimskog Carstva Charlesa V]]; Vesalije mu je predstavio prvu objavljenu kopiju (uvezanu svilom carske ljubičaste boje, sa posebnim ručno naslikanim ilustracijama koje se ne nalaze ni u jednoj drugoj kopiji). Kao pratnju za ''Fabrica'', Vesalije je objavio sažet i manje skup ''Epitom'': u vrijeme kada je objavljen 1543. godine, koštao je 10 [[batzen]]a.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Kusukawa |first1=Sachiko |title=De humani corporis fabrica. Epitome (CCF.46.36) |url=http://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/PR-CCF-00046-00036/1 |website=Cambridge Digital Library |accessdate=1 August 2016}}</ref> Kao rezultat toga, ''Epitom'' je postao šire viđen nego ''Fabrica''; sadržavao je osam anatomskih gravura koje su sažimale vizuelni materijal iz ''Fabrica'',jednu ilustraciju ljudskog skeleta uzetu direktno iz ''Fabrica'' i dva nova drvoreza.<ref>M. Kemp, "A drawing for the ''Fabrica''; and some thoughts upon the Vesalius muscle-men." ''Medical History'', 1970</ref> |

|||

A particular form of Renaissance architecture in Germany is the [[Weser Renaissance]], with prominent examples such as the [[Town Hall of Bremen|City Hall]] of [[Bremen]] and the [[University of Helmstedt|Juleum]] in [[Helmstedt]]. |

|||

== Očuvane kopije == |

|||

Više od 700 kopija očuvano je od izdanja iz 1543. i 1555. godine.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Margócsy |first=Dániel |last2=Somos |first2=Mark |last3=Joffe |first3=Stephen N. |date=August 2018 |title=Sex, religion and a towering treatise on anatomy |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05941-0 |journal=Nature |volume=560 |issue=7718 |pages=304–305 |doi=10.1038/d41586-018-05941-0}}</ref> Od njih, do 2018. nekih 29 kopija bilo je u Londonu, 20 u Parizu, 14 u Bostonu, 13 u New Yorku, 12 u Cambridgeu (Engleska) i 11 u Oxfordu i Rimu.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Margocsy |first1=Daniel |last2=Rankin |first2=Bill |title=New Money, Old Knowledge |url=http://www.radicalcartography.net/index.html?fabrica |website=Radical Cartography |accessdate=18 November 2018}}</ref> [[Biblioteka John Hay]] pri [[Univerzitet Brown|Univerzitetu Brown]] posjeduje kopiju [[antropodermička bibliopegija|uvezanu u štavljenu ljudsku kožu]].<ref name="MLJOHNSON">{{cite web <!--|DUPLICATE_url=http://www.timesargus.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20060108/NEWS/601080346/1003/NEWS02--> |title=Libraries own books bound in human skin |accessdate=2009-10-06 |last=Johnson |first=M.L. |date=2006-01-08 |work=The Barre Montpelier Times Argus |publisher=The Associated Press |url=http://www.timesargus.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20060108/NEWS/601080346/1003/NEWS02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060810191350/http://www.timesargus.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20060108/NEWS/601080346/1003/NEWS02 |dead-url=yes |archivedate=2006-08-10 }}</ref> |

|||

In July 1567 the city council of [[Cologne]] approved a design in the Renaissance style by Wilhelm Vernukken for a two storied loggia for [[Cologne City Hall]]. [[Michaelskirche (München)|St Michael]] in [[Munich]] is the largest Renaissance church north of the Alps. It was built by [[William V, Duke of Bavaria|Duke William V]] of [[Bavaria]] between 1583 and 1597 as a spiritual center for the [[Counter Reformation]] and was inspired by the Church of [[il Gesù]] in Rome. The architect is unknown. Many examples of [[List of Brick Renaissance buildings|Brick Renaissance buildings]] can be found in [[Hanseatic League|Hanseatic]] old towns, such as [[Stralsund]], [[Wismar]], [[Lübeck]], [[Lüneburg]], [[Friedrichstadt]] and [[Stade]]. Notable German Renaissance architects include [[Friedrich Sustris]], [[Benedikt Rejt]], [[Abraham van den Blocke]], [[Elias Holl]] and [[Hans Krumpper]]. |

|||

<center><gallery heights="200px" perrow="5" mode="nolines"> |

|||

File:De humani corporis fabrica (24).jpg |

|||

File:Fourth muscle man, by Vesalius. Wellcome L0001647.jpg |

|||

File:De humani corporis fabrica (25).jpg |

|||

File:De humani corporis fabrica (27).jpg |

|||

File:De humani corporis fabrica (26).jpg |

|||

</gallery></center> |

|||

== Utjecajni ljudi == |

|||

Neke od slika, iako razdvojene sa nekoliko stranica teksta, čine kontinuiranu panoramu pejzaža u pozadini kada se stave jedna do druge.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-30027161|title=The self-publicist whose medical text books caused a stir|publisher= BBC|access-date=25 November 2017}}</ref> |

|||

=== Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1398–1468) === |

|||

Rođen kao Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden,<ref>[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07090a.htm Johann Gutenberg] pri [[New Catholic Encyclopedia]]</ref> [[Johannes Gutenberg]] se naširoko smatra najutjecajnijom osobom u njemačkoj renesansi. Kao slobodni mislilac, humanista i izumitelj, Gutenberg je također odrastao u renesansi, ali je i snažno utjecao na nju. Njegov najpoznatiji izum je [[štamparska mašina]] iz 1440. godine. Gutenbergova mašina omogućila je humanistima, reformistima i ostalima da šire svoje ideje. Također je poznat i kao stvoritelj [[Gutenberg Bible]], ključnog djela koje je označilo početak "[[Printing press#Printing revolution|Gutenbergove revolucije]]" i doba štampane knjige u [[zapadni svijet|zapadnom svijetu]]. |

|||

=== Johann Reuchlin (1455–1522) === |

|||

[[Johann Reuchlin]] bio je svojedobno najvažniji aspekt podučavanja o svjetskoj kulturi u Njemačkoj. Bio je poznavalac i njemačkog i hebrejskog jezika. Poslije diplomiranja podučavao je u Baselu, te je smatran izuzetno inteligentnim. Ipak, nakon što je napustio Basel, morao je početi kopirati rukopise i naukovati unutar pojedinih područja prava. Međutim, najpoznatiji je po svom radu unutar istraživanja hebrejskog jezika. Za razliku od nekih drugih "mislilaca" svog vremena, Reuchlin se udubio u tu materiju i čak stvorio vodič za propovijedanje unutar hebrejske vjere. Ta knjiga, zvana ''De Arte Predicandi'' (1503), moguće je jedno od njegovih najpoznatijih djela iz tog perioda. |

|||

=== Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) === |

|||

[[Albrecht Dürer]] bio je u to doba, te je i ostao, najpoznatiji umjetnik njemačke renesanse. Bio je poznat širom Evrope, te veoma cijenjen u Italiji, gdje je njegov rad bio poznat uglavnom kroz njegovu [[Old master print|štampu]]. Uspješno je integrirao složen sjevernjački stil sa renesansnom harmonijom i monunmentalnošću. Među njegovim najpoznatijim djelima su ''[[Melencolia I]]'', ''Četiri jahača'' iz njegovog [[drvorez]]ne serije ''[[Apocalypse (Dürer)|Apokalipsa]]'', te ''Vitez, Smrt i Vrag''. Drugi značajni umjetnici bili su [[Lucas Cranach the Elder]], [[Danube School]] i [[Little Masters]]. |

|||

=== Martin Luther (1483–1546) === |

|||

[[Martin Luther]]<ref name="Plass">{{cite book |last=Plass |first= Ewald M. |chapter=Monasticism |title=What Luther Says: An Anthology |location=St. Louis |publisher=Concordia Publishing House |year=1959 |volume=2 |page=964 |ref=harv}}</ref> je bio protestantski [[reformacija|reformator]] koji je kritizirao crkvene prakse poput prodavanja indulgencija, protiv kojih je pisao u svojih [[The Ninety-Five Theses|''Devedeset pet teza'']] 1517. godine. Luther je također preveo [[Luther Bible|Bibliju]] na njemački jezik, učinivši kršćanske spise dostupnijima općoj populaciji i nadahnuvši standardizaciju njemačkog jezika. |

|||

== Povezano == |

|||

* [[Renesansni humanizam u Sjevernoj Evropi]] |

|||

== Reference == |

== Reference == |

||

{{ |

{{reflist|2}} |

||

== |

=== Izvori === |

||

{{Refbegin|40em}} |

|||

* O'Malley, C.D. ''Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-1564''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964. |

|||

* [[Giulia Bartrum|Bartrum, Giulia]] (1995); ''German Renaissance Prints, 1490–1550''; British Museum Press, 1995, {{ISBN|0-7141-2604-7}} |

|||

* Vesalius, Andreas. ''De humani corporis fabrica libri septem'' [Naslovna strana: ''Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, scholae medicorum Patauinae professoris De humani corporis fabrica libri septem'']. Basileae [Basel]: ''Ex officina'' Joannis Oporini, 1543. |

|||

* Bartrum, Giulia (2002), ''Albrecht Dürer and his legacy: the graphic work of a Renaissance artist'', British Museum Press, 2002, {{ISBN|978-0-7141-2633-3}} |

|||

* [[Michael Levey]], ''Painting at Court'', Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1971 |

|||

* Snyder, James; ''Northern Renaissance Art'', 1985, Harry N. Abrams, {{ISBN|0-13-623596-4}} |

|||

* [[Hugh Trevor-Roper|Trevor-Roper, Hugh]]; ''Princes and Artists, Patronage and Ideology at Four Habsburg Courts 1517–1633'', Thames & Hudson, London, 1976, {{ISBN|0-500-23232-6}} |

|||

* Wood, Christopher S. Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape, 1993, Reaktion Books, London, {{ISBN|0-948462-46-9}} |

|||

{{Refend}} |

|||

== Dalje čitanje == |

|||

*{{cite book |editor-last=O'Neill |editor-first=John P. |editor-link= <!-- NONE: DO NOT LINK -->|title=The Renaissance in the North | location=New York | publisher=The Metropolitan Museum of Art | date=1987 |isbn=0-87099-434-4 |oclc=893699130 |

|||

* Vesalius, Andreas. ''On the Fabric of the Human Body,'' preveli W. F. Richardson i J. B. Carman. 5 svezaka. San Francisco and Novato: Norman Publishing, 1998-2009. |

|||

|url=http://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15324coll10/id/113542}} |

|||

* Vesalius, Andreas. ''The Fabric of the Human Body. An Annotated Translation of the 1543 and 1555 Editions'', uredili D.H. Garrison i M.H. Hast, Northwestern University, 2003. |

|||

* Vesalius, Andreas. ''[http://www.biusante.parisdescartes.fr/vesale La Fabrique du corps humain (1543), livre I dans La fabrique de Vésale et autres textes]''. Prvi prevod na francuski jezik od strane J. Vons et S. Velut, Paris, BIU Santé, 2014. |

|||

== Vanjske poveznice == |

== Vanjske poveznice == |

||

{{Commonscat|position=left|Renaissance in Germany}} |

|||

* {{commonscat-inline|De humani corporis fabrica}} |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20100818075226/http://archive.nlm.nih.gov/proj/ttp/books.htm Turning the Pages ''Online'']. Projekat Nacionalne biblioteke medicine SAD za digitaliziranje slika i ploča iz "rijetkih i lijepih historijskih slika u biomedicinskim naukama". |

|||

* [https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/vesalius_home.html Andreas Vesalius. ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica.'' Historical Anatomies on the Web.] Odabrane slike iz izvornog djela. Nacionalna biblioteka medicine. |

|||

* [http://vesalius.northwestern.edu/ ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica'' online] — prevedena sa punim slikama, iz Sjeverozapadnog Univerziteta |

|||

* [http://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/content/pageview/6339659 Andreae Vesalii bruxellensis, scholae medicorum Patavinae professoris, de Humani corporis fabrica Libri septem], Basileae, ex officina Ioannis Oporini, juni 1543. |

|||

* [http://www.cppdigitallibrary.org/items/browse?advanced%5B0%5D%5Belement_id%5D=48&advanced%5B0%5D%5Btype%5D=contains&advanced%5B0%5D%5Bterms%5D=Vesalius%2C+Andreas%2C+1514-1564.+De+humani+corporis+fabrica Selected images from ''De humani corporis fabrica''] Iz Digitalne biblioteke Koledža liječnika Philadelphije |

|||

* [http://link.library.utoronto.ca/anatomia/ Anatomia 1522–1867: Anatomske ploče iz Biblioteke rijetkih knjiga Thomasa Fishera] |

|||

Verzija na datum 21 juli 2019 u 15:02

Također uraditi:German Renaissance, Renaissance in the Low Countries, Renaissance in Poland, Italian Renaissance, Portuguese Renaissance, Mid-Tudor Crisis, 19th-century London, History of London (1900–39)

Njemačka renesansa, dio sjeverne renesanse, bila je kulturološki i umjetnički pokret koji se proširio među njemačkim misliocima u 15. i 16. vijeku i koji se razvio iz talijanske renesanse. Mnoga područja umjetnosti i nauka bila su pod utjecajem, prije svega širenjem renesansnog humanizma u razne njemačke države i kneževine. Napravljeni su mnogi koraci naprijed u područjima arhitekture, umjetnosti i nauka. Njemačka je dovela do dvije pojave koje su dominirale 16. vijekom u čitavoj Evropi: štamparstvo i protestantsku reformaciju.

Jedan od najvažnijih njemačkih humanista bio je Konrad Celtis (1459–1508). Celtis je studirao u Kelnu i Heidelbergu, a kasnije je putovao čitavom Italijom prikupljajući latinske i grčke rukopise. Pod velikim utjecajem Tacita, koristio je knjigu Germania kako bi uveo njemačku historiju i geografiju. Na kraju je posvetio svoje vrijeme poeziji, gdje je hvalio Njemačku na latinskom jeziku. Još jedna važna ličnost bio je Johann Reuchlin (1455–1522) koji je studirao na različitim mjestima u Italiji i kasnije podučavao grčki jezik. Studirao je hebrejski jezik, sa ciljem da pročisti kršćanstvo, ali je naišao na protivljenje crkve.

Najvažniji umjetnik njemačke renesanse je Albrecht Dürer, naročito poznat po svojoj štampi u drvorezu i gravuri, koja se proširila čitavom Evropom, crtežima i slikanim portretima. U važnu arhitekturu iz ovog perioda spadaju Landshut Residence, Heidelberg Castle, Augsburg Town Hall kao i Antiquarium od Munich Residenz, najveća renesansna dvorana sjeverno od Alpa.[1]Šablon:Circular reference

Pozadina

Renesansa je većinom vođena obnovljenim interesom za klasično učenje i također je bila rezultat brzog ekonomskog razvoja. Na početku 16. vijeka, Njemačka (što se odnosi na zemlje sadržane unutar Svetog Rimskog Carstva) je bila jedno od najprosperitetnijih područja u Evropi unatoč relativno niskom nivou urbanizacije u usporedbi sa Italijom i Nizozemskom.[2]Šablon:Full Imala je koristi od bogatstva određenih sektora poput metalurgije, rudarstva, bankarstva i tekstila. Još važnije, štampanje knjiga razvilo se u Njemačkoj i njemački štampači dominirali su novom trgovinom knjigama u većini drugih država do duboko u 16. vijeku.

Umjetnost

The concept of the Northern Renaissance or German Renaissance is somewhat confused by the continuation of the use of elaborate Gothic ornament until well into the 16th century, even in works that are undoubtedly Renaissance in their treatment of the human figure and other respects. Classical ornament had little historical resonance in much of Germany, but in other respects Germany was very quick to follow developments, especially in adopting printing with movable type, a German invention that remained almost a German monopoly for some decades, and was first brought to most of Europe, including France and Italy, by Germans. [nedostaje referenca]

Printmaking by woodcut and engraving was already more developed in Germany and the Low Countries than elsewhere in Europe, and the Germans took the lead in developing book illustrations, typically of a relatively low artistic standard, but seen all over Europe, with the woodblocks often being lent to printers of editions in other cities or languages. The greatest artist of the German Renaissance, Albrecht Dürer, began his career as an apprentice to a leading workshop in Nuremberg, that of Michael Wolgemut, who had largely abandoned his painting to exploit the new medium. Dürer worked on the most extravagantly illustrated book of the period, the Nuremberg Chronicle, published by his godfather Anton Koberger, Europe's largest printer-publisher at the time.[3]

After completing his apprenticeship in 1490, Dürer travelled in Germany for four years, and Italy for a few months, before establishing his own workshop in Nuremberg. He rapidly became famous all over Europe for his energetic and balanced woodcuts and engravings, while also painting. Though retaining a distinctively German style, his work shows strong Italian influence, and is often taken to represent the start of the German Renaissance in visual art, which for the next forty years replaced the Netherlands and France as the area producing the greatest innovation in Northern European art. Dürer supported Martin Luther but continued to create Madonnas and other Catholic imagery, and paint portraits of leaders on both sides of the emerging split of the Protestant Reformation.[3]

Dürer died in 1528, before it was clear that the split of the Reformation had become permanent, but his pupils of the following generation were unable to avoid taking sides. Most leading German artists became Protestants, but this deprived them of painting most religious works, previously the mainstay of artists' revenue. Martin Luther had objected to much Catholic imagery, but not to imagery itself, and Lucas Cranach the Elder, a close friend of Luther, had painted a number of "Lutheran altarpieces", mostly showing the Last Supper, some with portraits of the leading Protestant divines as the Twelve Apostles. This phase of Lutheran art was over before 1550, probably under the more fiercely aniconic influence of Calvinism, and religious works for public display virtually ceased to be produced in Protestant areas. Presumably largely because of this, the development of German art had virtually ceased by about 1550, but in the preceding decades German artists had been very fertile in developing alternative subjects to replace the gap in their order books. Cranach, apart from portraits, developed a format of thin vertical portraits of provocative nudes, given classical or Biblical titles.[4]

Lying somewhat outside these developments is Matthias Grünewald, who left very few works, but whose masterpiece, his Isenheim Altarpiece (completed 1515), has been widely regarded as the greatest German Renaissance painting since it was restored to critical attention in the 19th century. It is an intensely emotional work that continues the German Gothic tradition of unrestrained gesture and expression, using Renaissance compositional principles, but all in that most Gothic of forms, the multi-winged triptych.[5]

The Danube School is the name of a circle of artists of the first third of the 16th century in Bavaria and Austria, including Albrecht Altdorfer, Wolf Huber and Augustin Hirschvogel. With Altdorfer in the lead, the school produced the first examples of independent landscape art in the West (nearly 1,000 years after China), in both paintings and prints.[6] Their religious paintings had an expressionist style somewhat similar to Grünewald's. Dürer's pupils Hans Burgkmair and Hans Baldung Grien worked largely in prints, with Baldung developing the topical subject matter of witches in a number of enigmatic prints.[7]

Hans Holbein the Elder and his brother Sigismund Holbein painted religious works in the late Gothic style. Hans the Elder was a pioneer and leader in the transformation of German art from the Gothic to the Renaissance style. His son, Hans Holbein the Younger was an important painter of portraits and a few religious works, working mainly in England and Switzerland. Holbein's well known series of small woodcuts on the Dance of Death relate to the works of the Little Masters, a group of printmakers who specialized in very small and highly detailed engravings for bourgeois collectors, including many erotic subjects.[8]

The outstanding achievements of the first half of the 16th century were followed by several decades with a remarkable absence of noteworthy German art, other than accomplished portraits that never rival the achievement of Holbein or Dürer. The next significant German artists worked in the rather artificial style of Northern Mannerism, which they had to learn in Italy or Flanders. Hans von Aachen and the Netherlandish Bartholomeus Spranger were the leading painters at the Imperial courts in Vienna and Prague, and the productive Netherlandish Sadeler family of engravers spread out across Germany, among other counties.[9]

In Catholic parts of South Germany the Gothic tradition of wood carving continued to flourish until the end of the 18th century, adapting to changes in style through the centuries. Veit Stoss (d. 1533), Tilman Riemenschneider (d.1531) and Peter Vischer the Elder (d. 1529) were Dürer's contemporaries, and their long careers covered the transition between the Gothic and Renaissance periods, although their ornament often remained Gothic even after their compositions began to reflect Renaissance principles.[10]

Arhitektura

Renaissance Architecture in Germany was inspired first by German philosophers and artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Johannes Reuchlin who visited Italy. Important early examples of this period are especially the Landshut Residence, the Castle in Heidelberg, Johannisburg Palace in Aschaffenburg, Schloss Weilburg, the City Hall and Fugger Houses in Augsburg and St. Michael in Munich, the largest Renaissance church north of the Alps.

A particular form of Renaissance architecture in Germany is the Weser Renaissance, with prominent examples such as the City Hall of Bremen and the Juleum in Helmstedt.

In July 1567 the city council of Cologne approved a design in the Renaissance style by Wilhelm Vernukken for a two storied loggia for Cologne City Hall. St Michael in Munich is the largest Renaissance church north of the Alps. It was built by Duke William V of Bavaria between 1583 and 1597 as a spiritual center for the Counter Reformation and was inspired by the Church of il Gesù in Rome. The architect is unknown. Many examples of Brick Renaissance buildings can be found in Hanseatic old towns, such as Stralsund, Wismar, Lübeck, Lüneburg, Friedrichstadt and Stade. Notable German Renaissance architects include Friedrich Sustris, Benedikt Rejt, Abraham van den Blocke, Elias Holl and Hans Krumpper.

Utjecajni ljudi

Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1398–1468)

Rođen kao Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden,[11] Johannes Gutenberg se naširoko smatra najutjecajnijom osobom u njemačkoj renesansi. Kao slobodni mislilac, humanista i izumitelj, Gutenberg je također odrastao u renesansi, ali je i snažno utjecao na nju. Njegov najpoznatiji izum je štamparska mašina iz 1440. godine. Gutenbergova mašina omogućila je humanistima, reformistima i ostalima da šire svoje ideje. Također je poznat i kao stvoritelj Gutenberg Bible, ključnog djela koje je označilo početak "Gutenbergove revolucije" i doba štampane knjige u zapadnom svijetu.

Johann Reuchlin (1455–1522)

Johann Reuchlin bio je svojedobno najvažniji aspekt podučavanja o svjetskoj kulturi u Njemačkoj. Bio je poznavalac i njemačkog i hebrejskog jezika. Poslije diplomiranja podučavao je u Baselu, te je smatran izuzetno inteligentnim. Ipak, nakon što je napustio Basel, morao je početi kopirati rukopise i naukovati unutar pojedinih područja prava. Međutim, najpoznatiji je po svom radu unutar istraživanja hebrejskog jezika. Za razliku od nekih drugih "mislilaca" svog vremena, Reuchlin se udubio u tu materiju i čak stvorio vodič za propovijedanje unutar hebrejske vjere. Ta knjiga, zvana De Arte Predicandi (1503), moguće je jedno od njegovih najpoznatijih djela iz tog perioda.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

Albrecht Dürer bio je u to doba, te je i ostao, najpoznatiji umjetnik njemačke renesanse. Bio je poznat širom Evrope, te veoma cijenjen u Italiji, gdje je njegov rad bio poznat uglavnom kroz njegovu štampu. Uspješno je integrirao složen sjevernjački stil sa renesansnom harmonijom i monunmentalnošću. Među njegovim najpoznatijim djelima su Melencolia I, Četiri jahača iz njegovog drvorezne serije Apokalipsa, te Vitez, Smrt i Vrag. Drugi značajni umjetnici bili su Lucas Cranach the Elder, Danube School i Little Masters.

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

Martin Luther[12] je bio protestantski reformator koji je kritizirao crkvene prakse poput prodavanja indulgencija, protiv kojih je pisao u svojih Devedeset pet teza 1517. godine. Luther je također preveo Bibliju na njemački jezik, učinivši kršćanske spise dostupnijima općoj populaciji i nadahnuvši standardizaciju njemačkog jezika.

Povezano

Reference

- ↑ Munich Residenz

- ↑ German economic growth, 1500–1850, Ulrich Pfister

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 Bartrum (2002)

- ↑ Snyder, Part III, Ch. XIX on Cranach, Luther etc.

- ↑ Snyder, Ch. XVII

- ↑ Wood, 9 – this is the main subject of the whole book

- ↑ Snyder, Ch. XVII, Bartrum, 1995

- ↑ Snyder, Ch. XX on the Holbeins, Bartrum (1995), 221–237 on Holbein's prints, 99–129 on the Little Masters

- ↑ Trevor-Roper, Levey

- ↑ Snyder, 298–311

- ↑ Johann Gutenberg pri New Catholic Encyclopedia

- ↑ Plass, Ewald M. (1959). „Monasticism”. What Luther Says: An Anthology. 2. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House. str. 964.

Izvori

- Bartrum, Giulia (1995); German Renaissance Prints, 1490–1550; British Museum Press, 1995, ISBN 0-7141-2604-7

- Bartrum, Giulia (2002), Albrecht Dürer and his legacy: the graphic work of a Renaissance artist, British Museum Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-7141-2633-3

- Michael Levey, Painting at Court, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1971

- Snyder, James; Northern Renaissance Art, 1985, Harry N. Abrams, ISBN 0-13-623596-4

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh; Princes and Artists, Patronage and Ideology at Four Habsburg Courts 1517–1633, Thames & Hudson, London, 1976, ISBN 0-500-23232-6

- Wood, Christopher S. Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape, 1993, Reaktion Books, London, ISBN 0-948462-46-9

Dalje čitanje

- O'Neill, John P., ur. (1987). The Renaissance in the North. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-434-4. OCLC 893699130.